Meet Ralph – Our Gold-Medal-Winning Chief Engineer

Over a Zoom call, Ralph DiDomenico shared his experiences in the engineering industry, his accomplishments, and what’s on the horizon for building operations and management. Read the journey that starts with inquisitiveness, harnesses diligence, and finishes on the podium. Meet Ralph: Aetos Imaging's Gold-Medal-Winning Chief Engineer.

Talk about how you started your career.

I started my career as a general contractor in 1984, so I was self-employed for about 12 years. And then in the 80s things got bad, so I gave up the business and got a job at 399 Park Ave. as a helper. I started there in ‘96, and I wasn’t able to operate on a lot of the machines because I didn’t have the right license, so I set out to get an engineer’s license.

I found out you had to take a test after 2 ½ years of work, so I got the book that was 3 or 4 inches thick, and I studied it every opportunity I had. To make a long story short, when I actually went to take the test, I knew the answers to most of the questions before I even finished reading them.

I passed, got my license, and my first job was at a bank on Central Park West. It was a one-man job and the place was demoed out and just filthy. I got to the point where I couldn't stand how dirty it was, so I made them give me a dumpster. And I ended up loading it 12 times with all the junk and debris inside the building. I actually cleaned it out and got new cabinets, swept everything up, and remodeled the bathrooms.

The gal in charge of the bank called up my boss and said I was trying to take over the building - making all these changes. My boss calls me up and asks me what's going on. So what do I do? I had him come down to the building and showed him everything I did to make the building better. He told me the place looked beautiful and he wasn't sure what the problem was.

I actually took pictures of the place before I did any changes, just in case something came up. I showed him what it used to look like and he told me not to listen when people complain about a job well done. I think that was a big encouragement for me in the future to make things better when I saw a problem.

Where did your career take you next?

Next, I interviewed and got a job at 11 Madison. They told me I’d have the assistant chief position, so I took the opportunity. I figured I'd rather go for the next level than stay where I was.

When I joined, the senior chief was having a hard time health-wise, so I spent 2 or 3 years covering for him. When he ended up retiring, they bumped me up to the top, and I spent the next 23 years there. I moved from assistant to senior chief in way less time than what I thought when I was interviewing and hired.

What did the new position look like? You weren’t sweeping or knocking out walls, were you?

No, not anymore. My primary job was to get everything up and running, all the equipment and machinery. MetLife demoed out the entire building: took everything out and put in new equipment. We had to go through each system, modify it, get it all working properly, test it, bring in a new BMS, new risers, new pumps, new chillers – everything was new. We had to see what was lacking in every system. I needed to install flash tanks for the steam system, vacuum pumps, things like that.

I also was in charge of reviewing blueprints, making sure they conformed to our BMS, approving wall locations that weren’t blocking our critical elements, and making sure their operations are compatible across systems. Taking that job at 11 Madison and moving up was a big challenge, but I really enjoyed all the new work I got to do and all the people I got to work with.

So you started as a general contractor, then became a helper, and now you find yourself doing huge building facilities management. How did your career grow or change from what you expected when you first started?

It was definitely a learning curve. But luckily I was always good mechanically. As a 12-year-old, I really started to get into mechanical things. Once I took apart our lawn mower down to the smallest pieces that I could. When my father came home, he looked at me and said, “You better make sure that thing runs.” And it did! I could put it all together without a problem.

When I was in High School, I was studying to do aviation power plant maintenance. I was always mechanically inclined: I could look at stuff – like pumps or fans or other equipment – and figure it out.

So as a helper at 399 Park, I actually used my education with aviation power plant maintenance to show my chief how to better align fan blades and make them run more efficiently. I had a system for how we did it, and he liked it so much we did it to every fan in the building. Now, the other engineers didn't really appreciate all the extra work, but it was good to go through and make things better.

Did you always have a knack for improving mechanical items?

Yeah for the most part, but I got a lot of help from the old-timers who knew what they were doing. A lot of them took me under their wing and showed me how to follow certain procedures, and some tricks of the trade: like changing gaskets with teflon, or preventing rust from accumulating on bolts.

As a senior level engineer, I was never a guy who – when a contractor came in to do their work – would say, “Do what you need to do" and just leave them to work in my building; I was always looking over their shoulder and learning a thing or two. I’d pick up ideas. I’d ask questions. I wanted to know what they were doing, and maybe learn how to run my equipment better.

You were at the senior level for over two decades. What is something you are proud of in your career?

I’m proud of the installation and operation of the ice plant at 11 Madison. We had 64 tanks that we dropped in through the elevator shaft, and completely changed the machines that were in there. I’m proud of it because it exceeded what was expected. It was done ahead of schedule, and it finished under budget. And the energy that is being saved is much better than what was expected as well. They’re saving nearly $800,000 a year in electric costs.

What was really cool is we built an atmosphere that was a friendly competition between the engineers on shift. They began trying to change pressures and other variables to make the system more efficient. And when the night shift saw the numbers of the day shift, they thought “Oh we can beat that”; it just created an environment of friendly competition where everybody wins.

Oh I was awarded the chief engineer award for BOMA in 2020. I’m pretty proud of that.

(Editor’s Note: Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) is “a federation of U.S. local associations and global affiliates”, and a BOMA award is “Considered one of the most difficult industry recognitions to earn.” So, basically, Ralph got the Gold Medal at the Building Olympics, something that is considered both really hard to do, and a really prestigious honor. Ralph was awarded in 2020 for Chief Operating Engineer of the Year while part of SL Green Realty Corp.)

If you could change one thing about the way buildings are run, what would it be?

I would tell them to be more penny-wise and less dollar-foolish. I’ve known management companies that take a dying lightbulb from one lamp and put it in another, whereas some companies go in and re-lamp the whole room. I know that everything is about the dollar, the dollar, the dollar – and to a point I can understand that. But sometimes you have to not be so cheap, and do a little more to help the whole company.

For example, add another knowledgeable engineer to the team so there is less pressure for everyone involved. Yeah, I know it costs to hire someone else on, but the building and the workers benefit -- especially if the new guy is highly experienced.

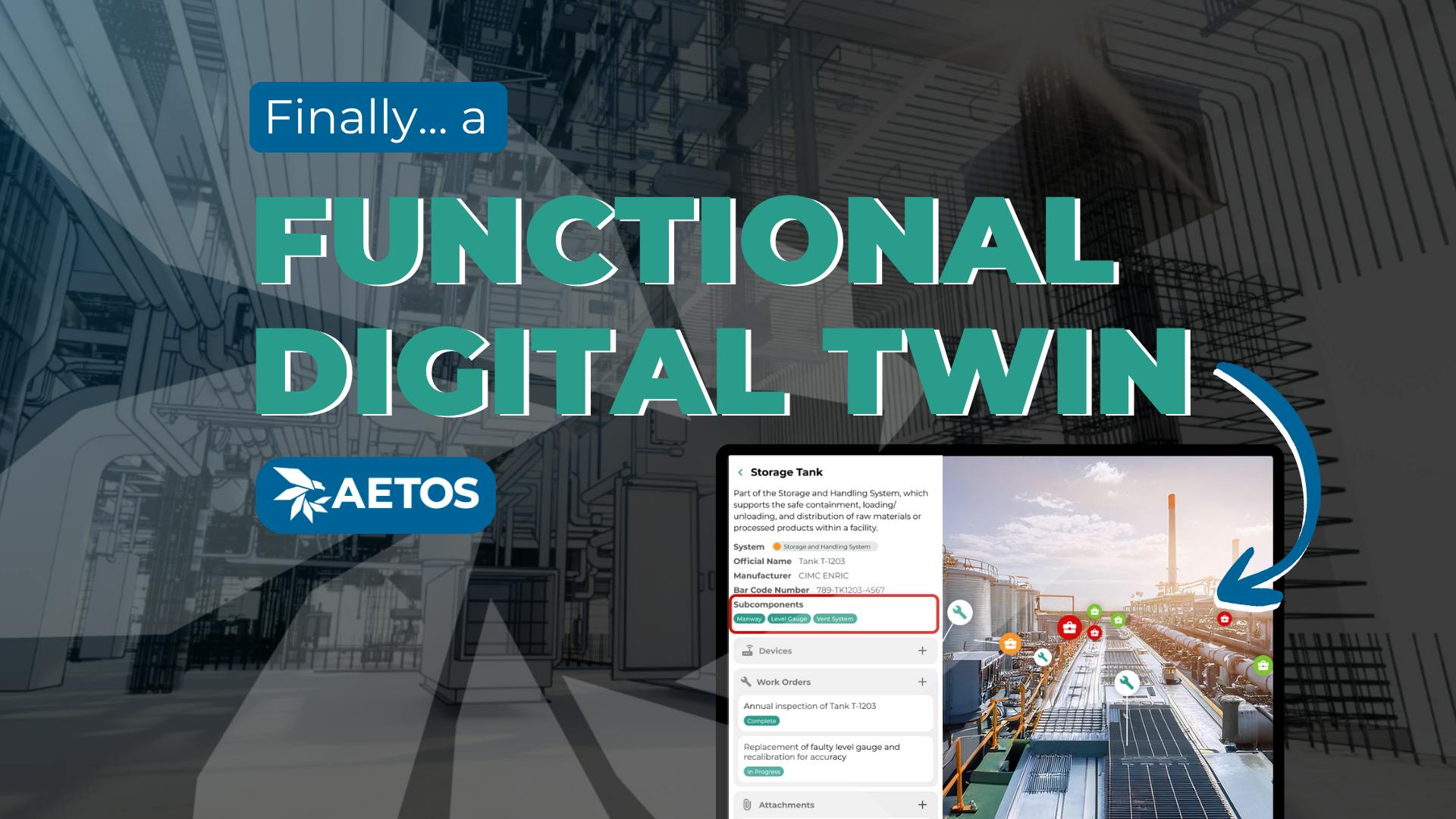

You're our Chief Engineer here at Aetos Imaging. Where do you see the value in Operate?

It puts everybody on the same knowledge level. We have a way to help and teach every worker the best way to do things. With our courses, we can bring in knowledgable veterans who can show you exactly how to do something, exactly where you need to do it. We’re trying to teach everyone how to do the important tasks the most efficient way possible.

Also, with new people coming into a structure, it teaches them exactly where all the equipment is in the building, teaches them how to do the PMs on them, and keeps them safer because we’re showing them how to operate in the space.

Where do you anticipate building operations and management is headed in the future?

Well, there’s an old saying: you need a shovel to dig a hole. There’s only so much software that you can write, there’s only so many matrices. Buildings will always need somebody there to check a fuse, pull it out, and change it.

Software like Operate will educate the workers, but you’re still going to need trained people in the field. The guy who is turning the wrench isn’t going away, so it’s up to companies like ours to instruct employees who are actually doing the work.